London Curiosities

“Be curious, always! For knowledge will not acquire you; you must acquire it.”

Sudie Back.

If you walk along St Martin's Le Grand in the City of London you will come to Postman's Park, which seems out of place in this busy commercial area. Inside the park was once the old Roman burial ground of St Botolph's churchyard. If the gate is open you may go in, where you will find some gravestones stacked by the side. They were moved during the rebuilding of the area after heavy bombing during the Second World War. George Watts was one of Victorian society's most popular and successful artists. His fame increased in 1864 when he married the popular actress Ellen Terry - though this marriage lasted less than a year. His work, in general, had a high tone of morality, from his works in the Tate and Victoria and Albert Museum, and his 'Physical Energy' sculpture in Kensington Gardens. In 1900 he was prompted to take over a wall in Postman's Park near to St Paul's, and then had it filled with delicate tiles honouring 'heroic deeds of self-sacrifice.' He died in 1904 with thirteen tiles going up in his lifetime. His widow kept adding to them until they ceased with no. 54. There is also a wooden statue of Watts. If you click on the seat below you will see enlarged photos of all the seats, and will be able to read most of them.

Postman's park seats - Click on seat for full seat inscriptions

Postman's park seats - Click on seat for full seat inscriptions

Stacked up graves in Postman's park

Another hidden corner of London is the street by the name of Cloth Fair, which runs by the side of West Smithfield. It has these two buildings that have survived the Great Fire of London in 1666. The houses at numbers 41 and 42 were built between 1597 and 1614, and were preserved from the Great Fire because they were enclosed by the wall of the priory of St Bartholomew.

St Bartholomew's gatehouse that leads to the oldest parish church in London - St Bartholomew-the-Great - was built in the sixteenth century and is where Queen Mary ate chicken and drank red wine while watching Protestant martyrs burn at the stake. The actual spot where they suffered (found in 1849) was in the roadway, a little left of the front of the gateway,

It was only when a first World War German Zeppelin bomb fell nearby in 1916 that the tiles to this arch fell off to reveal this Elizabethan half-timber-fronted house built in 1597.

Front and rear view of the Elizabethan gate house

The Brixton Windmill was built in 1817 and leased to Mr John Ashby. John, his sons and grandson were millers producing stone-ground wholemeal flour. The Ashby family operated the mill, which became known as ‘Ashby's Mill’ for the whole of its working life. By 1862 the surrounding area had become too built up for the windmill to operate efficiently, so the building was used for storage. In 1962, the windmill was acquired by the London County Council. The mill is now owned by Lambeth Borough Council and forms the centrepiece of Windmill Gardens. With nearby Brixton Prison and the very busy Brixton shopping centre, this windmill remains a hidden gem of South London.

Side by side they stand and more than a century apart are these two milestones. One was erected in the reign of the Prince Regent, later George IV, and placed in Regent's Park - before the architect, Nash, laid it out as a Royal Palace for the Regent, who decided to open it out as a Royal Park. The other was erected in the reign of Queen Victoria. Regent's Park (including Primrose Hill) covers 487 acres.

Ask any visitor to London what is the biggest clock in London and you will most likely get the answer Big Ben. Big Ben - the official name being St Stephen's Tower - is the most famous of the London clocks. However, the biggest clock face belongs to Shell Mex house in The Strand, once the London head office of the Shell petroleum company, opened in 1933, with a tower rising to over 200 ft and containing the largest clock in London.

They stand on opposite corners of the west window of St Andrew's Church, St Andrew's Hill. These figures are to be found in various parts of London, on the walls of school buildings. This would mean that this church once had a school for girls and boys. The boy holds a Bible in his right hand and a cap in his left.

The girl has a Bible in her right hand and what appears to be a shopping bag in the other. She stands looking at the new Sainsbury's head office at Holborn Circus, which has an express shop inside. She has a look of surprise in her eyes as though she has forgotten to buy something that she needed.

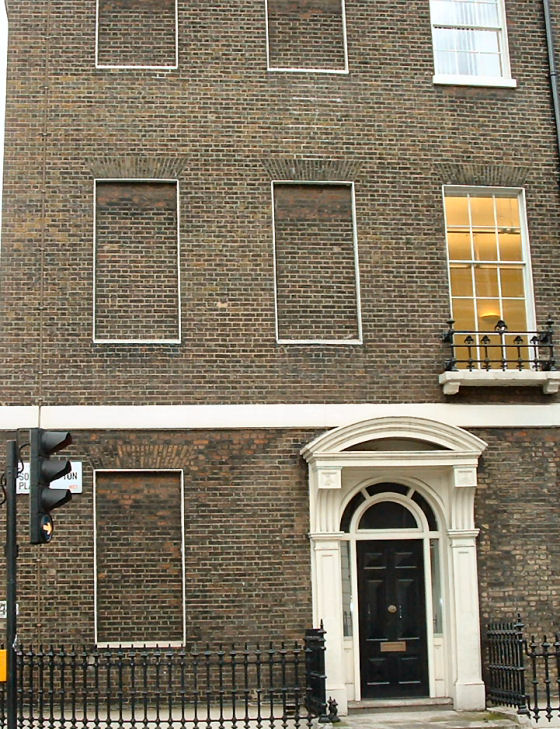

William III was in a financial crisis in 1696 due to the wars with Ireland and on the continent. One new idea that was brought in to help pay for the debt was the unpopular window tax, or as some people called it; 'Daylight Robbery'. The tax was payable on houses of more than six windows, so the clever tax-dodgers simply got hold of a builder to brick up the other windows. Houses with nine windows would pay 2/- (10p) and for ten to nineteen windows the cost was 4/- (20p). In 1851 the window tax was scrapped and a new tax called house duty, a forerunner of the community charge, became payable.

The old tramway that passed under the centre of the road in the Kingsway was built in 1906. The Kingsway Tramway Subway was opened to the public on 24th February, 1906 and continued in service until 5th April, 1952.

It was a two-way tunnel that took trams down to the Victoria Embankment underneath Waterloo Bridge, where they could go either left to Blackfriars or right to Westminster. The last tram entered the tunnel on 5th of April 1952. Part of the tunnel was opened to cars in 1964 from Waterloo Bridge, becoming known as the Strand Underpass, though it ends quite short of the old entrance. It has had various uses such as films and storage and still has the tracks left from those bygone days.

Magpie Alley that cuts between Bouverie Street and Whitefriars Street has a hidden treasure, for beneath the railings of a new office development, down in the basement is this 700-year-old crypt displayed in a glass case. This is the only remains of the Whitefriars Monastery that has lain hidden for hundreds of years beneath a house, where the vault was used as a coal cellar. This medieval crypt offered sanctuary in the Middle Ages for thieves, murderers, and prostitutes as the lawmen of those times were afraid to enter this monastic crypt.

The Oxo Tower is now a top class London restaurant with superb views across the River Thames of the city of London. Built on an earlier twentieth-century electric power station and rebuilt in 1920 with its art nouveau design by the Oxo meat and gravy consortium owned by the Liebig meat company. Unable at the time to have outside advertising on such a high tower, the company used the clever window design in the Oxo letters, which was allowed, whereby the red background light illuminates the Oxo sign at night to the London skyline as our picture insert shows.

The Jewel Tower was built in 1365-6 to house jewels and treasures of gold and silver belonging to King Edward III and is the only surviving building of the ancient private palace of Westminster. It is surrounded by an attractive moat that is fed by the Tyburn during heavy rainfall. It was the southernmost end of the palace, hence its L-shape. Other than a treasury, it has also been the storeroom for House of Lords documents and was used by the Weights and Measures department. It is now open to the public as a museum.

Outside the Athenaeum Club in Waterloo Place is this strange pair of kerbstones that have stood here for over 170 years with people passing by without a thought. They were placed in this position to allow the Duke of Wellington to both mount and dismount his horse while visiting the Athenaeum club. The Dublin-born Iron Duke defeated Napoleon at Waterloo in June 1815.

One of the most beautiful gas lampposts to remain in use in London is this one in Carting Lane off Savoy Hill. It is one of the last surviving gas lamps to be using gas from effluent in the subterranean sewers.

On the corner of Queen Victoria Street and Huggin Hill is a small open space that is popular with city office workers on a warm sunny day. Here they can relax with their sandwiches and chill out during their lunch break. The reason for this quiet garden retreat? A large Roman bathhouse once stood here, fed by a natural spring. Much of this bathing complex still remains hidden in the basement of the buildings opposite. In the meantime, we can still glimpse part of the Roman wall at the bottom of the gardens.

This fine shop doorway complete with area railings has all the elegant beauty of eighteenth-century architecture including a window box displaying summer flowers. As interesting as this corner shop may be, I am drawn to the old sign above the Barbon Close W.C.1 plate which informs us that G Bailey and Sons, Horse and Motor Contractor, were once operating in the rear mews. The wonderful thing about London is that this old sign remains because nobody has considered removing it even though the days of horse-drawn vehicles are long gone.

This wonderful piece of Southbank history had remained hidden until a warehouse building was destroyed in a World War Two raid, revealing itself while the warehouse bricks were being removed. The rose window was part of the lavish fourteenth-century Great Hall that served the Bishops of Winchester as the central feature of their London Palace. Southwark in those days was full of brothels known as stews. There were the famous theatres, the Rose and the Globe, and bull-baiting just a stone's throw away. The bishops decided to build a prison that became known as The Clink just to the west of the palace. The last bishop to reside here was Lancelot Andrewes, who died in 1626. In 1642 Cromwell used it to house Royalist prisoners and eventually sold it off to a Camberwell property speculator who broke up the palace leaving it a ruin by 1662. If the wall had not been used to support the inner sanctums of a warehouse wall this unique Elizabethan gem would not have survived.

Jacob the Circle Dray Horse.

The famous Courage dray horses were stabled on this site from the early nineteenth century. They delivered beer around London from the brewery on Horselydown Lane by Tower Bridge. In the sixteenth century, the area became known as Horselydown, which derives from 'horse-lie-down', a description of working horses resting before crossing London Bridge into the City of London.

In 1811 Daniel Alexander built a warehouse to store tobacco, wines and spirits. The warehouse still survives although it had a facelift in the mid-eighties when some £30 million were spent to convert the building into a modern shopping mall. It proved to be a disaster and the area now remains one of the quietest spots in this vicinity. At the rear of the warehouse are a couple of replica ships. The one in our picture is the Three Sisters, the original of which was built a couple of miles away at Blackwall Yard in 1788. It sailed to the East and West Indies with British home-made goods and returned with tobacco and rum.

Relics of the old warehouse wall with a few barrels of rum balancing on top.

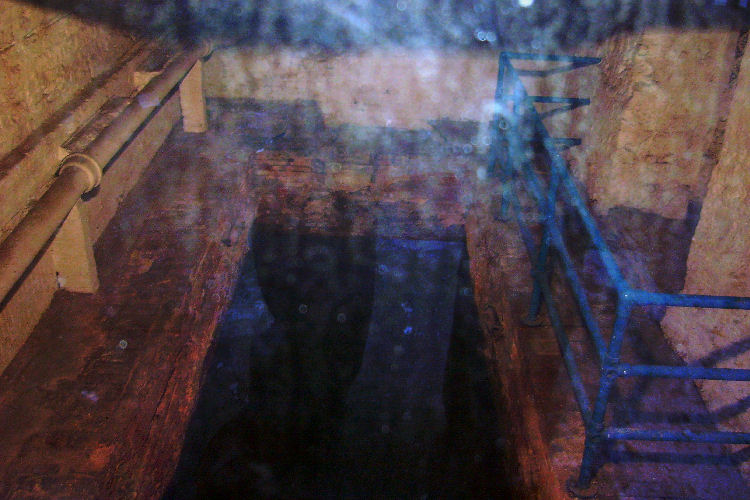

The view of the mysterious bath through the window.

At the top of Strand Lane is a house with an old window that reveals what is purported to be a Roman bath. It was certainly here in the seventeenth century, that much we do know, though the preceding years remain a bit of a mystery. It is surrounded by some typical Roman tiles so it could well come from those distant times. However, this theory has been dismissed several times by archaeologists.

The view through the cloudy window and a well worn frame of the mysterious bath.

We do know that the bath was once replenished from a small stream said to be Holy Water that came from St Clement's well that passes underneath St Clement Danes church in The Strand. What we also know is that the bath was found on the site of Arundel House later to become Norfolk House, home to the Dukes of Norfolk. During the reign of Charles II, Norfolk House was demolished, at which time the underground bath was first exposed. It is thought to have been a covered over water-storage reservoir from its older Arundel House times. The stream that once flowed down Strand Lane was much wider than the lane of today, and the water would run along its path into the Thames.

The Ferryman's Seat Bear Gardens, Bankside.

The Ferryman’s seat along at Bankside near to where Shakespeare’s Globe now stands, has seen rather a lot of comings and goings. Long ago, when there was only London Bridge to cross the river, there were many ferrymen waiting to take people from one side to the other. It would have been among the many “stews”, the old name for brothels, that were lined along this side of the river on the South Bank, as well as actors and troubadours that performed at the Rose and the Globe theatres, with the large crowds that also came from the nearby bear-baiting ring. Now it is set into the side of a modern building in exactly the same spot where the ferrymen rested all those years ago.

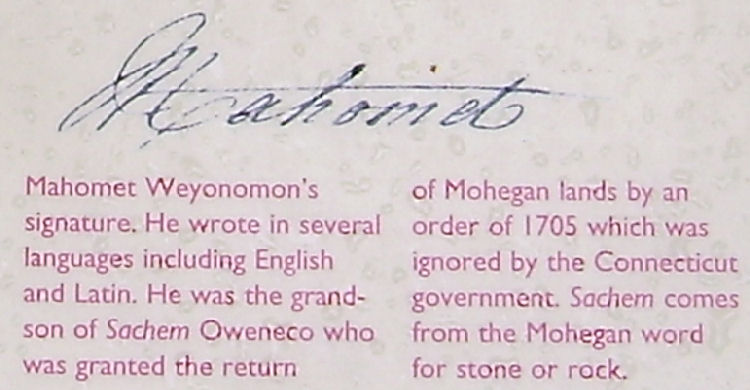

The curious stone circle of Mohegan Chief, Mahomet Weyononon remembered at last.

In 1736 Mahomet Weyonomon, a Mohegan Sachem (chief), died in Aldermanbury in the City of London. He was 36 years old. Foreigners could not be buried in the City, so he was carried across the river and buried near St Saviour’s church, now Southwark Cathedral. Mahomet had sailed to London to petition King George II for the return of stolen lands taken by early English settlers. His tribe had helped the first English settlers in New England to survive the bitter cold and repel Indian attacks. Despite support from Queen Anne’s Commissioners in 1705, the lands were not returned. While waiting for an audience with King George II, Captain John Mason and Mahomet contracted smallpox and died. Two hundred and seventy years later a stone was brought from Mohegan lands and carved with forms that reflect ancient tribal customs. The stone was unveiled on 22 November 2006 by the Queen, accompanied by the Duke of Edinburgh, with tribal chairman Bruce “Two Dogs” Bozsum, who presented the queen with a red stone peace pipe, and with the U.S. Ambassador - symbolically granting the audience Mahomet never received. "Mahomet has his stone now – and his place in history,” said Bozsum.

The original street bollards were adapted from the French cannons captured at the Battle of Trafalgar in 1805. They were placed on street corners to stop the iron wagon wheels of carts mounting the kerbs and doing damage. They proved so popular that they adorned many of the London streets and, once the real cannons were all used up, copies were made and are still to be seen on the streets of London today. They continue to be made today in the same familiar shape, although today’s replacements are now of the plastic variety. The one pictured above, however, is an original French cannon which stands on the Southbank near to Shakespeare’s Globe.

This metal lighthouse tower is more than fifty miles from the nearest coast and opposite Kings Cross Station. It has puzzled the passing populations for many years, with nobody knowing why it was erected in the first place. Some will tell of the helter-skelter fairground ride that is said to have been here in early Victorian times. Others claim that the shop below was once an oyster restaurant and that the lighthouse was added for effect. I have even heard it said that an old seafaring sailor, pensioned out of the navy, had this eccentric loft conversion built to remind him of his beloved voyages. Now a listed building and in a state of disrepair, with the entire building recently undergoing renovation With the Channel Tunnel mainline rail station across the road, and with its direct line to Paris, you would think it could be returned to an oyster bar once again.

North Kensington can boast the only remaining 19th-century tile kiln in London. Originally known as the Piggeries and Potteries where high-quality clay was dug from about 1818, and then fired in this very kiln that still stands in Walmer Road. Once known as Cut-throat Lane, Pottery Lane nowadays has properties selling from anything upwards of £500,000. When Samuel Lake, whose rough trade of scavenging and chimney-sweeping compelled him in the early years of the nineteenth century to remove himself from premises in Tottenham Court Road, and set up a business in a more solitary spot here at Nottingdale, where gravel and sand were discovered under the grass, and soon his brickworks was making bricks for the wealthy owners of houses being built in North Kensington. The pig-keepers of Tyburnia, present-day Marble Arch and Bayswater Road, soon made use of this district. Meanwhile, some sixteen acres of adjoining land to the west were being dug for the brick earth by Stephen Bird, one of the principal brick makers in London, who was also a builder active in Kensington. With the arrival of the potters, several of the principal ingredients were soon put together. Many of the workforce employed were Irish labourers who could also turn their hands to bricklaying and building work, and so from this little acorn, North Kensington grew.

On the corner of a building almost opposite the Old Curiosity Shop is another amazing curiosity that goes unnoticed by most city dwellers. It is an old metal sign claiming that orders are taken for the dispatch of newspapers, books and magazines to all parts of the world. For this building was from 1929 to 1976 the headquarters of Messrs W. H. Smith & Son and the shrapnel-damaged sign that is still attached to the wall is now all that remains to remind us of the business that stood here on the night of the German air raid on 10 October 1940.

The swastika fixed to the wall of the Indian High Commission, India House, in Aldwych. The motif was cast long before the Nazi Party took over German politics during the 1930s, leading to Hitler’s rise to power with the Third Reich. The swastika was used as a religious symbol thousands of years ago and still commands reverence in several regions of Asia. It has been found drawn on caves dating from the Neolithic times, where it was said to be a symbol of good luck. It is only good luck which kept this sign on this building throughout the war years and beyond when it was once deemed a fascist icon and protesters called for its removal. It now blends in well with the rest of the motifs along this wall that go largely unnoticed.

Not long after the Great Fire of London in 1666, it was deemed important to differentiate between houses covered by insurance and those that were not, in order for firemen to battle the fire of insured properties first. In 1697 it is recorded that the Hand-In-Hand Society ordered their treasurer to "pay for two hundredweight of lead eighteen shillings and for ye making of markes for ye Society". Men who went around with ladders to fix them on buildings often charged the clients a fee for their prompt services, otherwise, if a fire ensued, and there was no metal mark found, then insurance would not be paid, and properties were not insured until the metal mark was affixed to the outside wall. In the days when addresses were given as vague directions like "on the south side of the road at Moulsey aforesaid between the Church and the Sign of the Swan", although the house in question was quite a distance from the church, so some form of identification was truly needed to establish the correct insured property. The fixing of plates on insured property gradually died out during the nineteenth century, although one or two companies still continued to do so almost to the turn of the century.

Albert Bridge, nicknamed "The Trembling Lady" because of its tendency to vibrate when large numbers of people walked over it, has signs on both sides of the river entrances which warned troops to break step whilst crossing the bridge.

Built as a toll bridge, it was commercially unsuccessful.

Six years after its opening it was taken into public ownership and the tolls were removed. The tollbooths still remain in place and are the only surviving examples of bridge tollbooths in London. Despite the many calls for its demolition or pedestrianisation, the Albert Bridge has remained open to vehicles throughout its existence, other than for brief spells during repairs. It is one of only two Thames road bridges in central London never to have been replaced.

Like so many of London’s ancient monuments that get overlooked without any signage to reveal as to its former use, is this ancient ruin of the Manor House of King Edward III (1527-79). Situated just off Bermondsey Wall East, and opposite the famous Angel public house, this once moated manor house was built in 1353. Standing alongside the banks of the river Thames, with the excavated foundations clearly visible; only now being constantly overlooked by a row of townhouses.

The 1706 Sundial that tells the wrong time.

On the south wall of St Katherine Cree in Leadenhall Street, is a curious triangular arrangement of brass rods which on close inspection proves to be a sundial, with the motto 'Non-Sine Lumine'.

This was put up in 1706, but over the years this narrow thoroughfare has been overshadowed by some high buildings opposite. It is therefore only at certain times of day that the dial is able to function correctly.

Site of the Royal Cockpit

Built during the 18th century, the Royal Cockpit stood alongside Birdcage Walk. Cock-fighting was first established in Tudor times and was a popular way to make money, as betting was heavy and the sport well regulated. The cocks would have to be of the same height and weight, and with their wings and tail trimmed. Public opinion turned against the sport during the 19th century with an Act of Parliament banning cruelty to animals in 1849, thus making cock-fighting illegal. The Royal Cockpit itself, however, was demolished in 1816, although not completely, and these narrow stone steps at Queen Anne’s gate which once led into it still remain.

Coal Hole

Once a regular feature in every street, cast iron coal hole hatches, set into the pavement, were used for unloading coal from the cart directly to the coal cellar, thus avoiding the dusty coal sacks being carried through the house. The design of the coal hatch would vary from house to house and street to street. Their style would generally reflect the household income. The hatches are locked from the inside to prevent them being lifted from the street. They were in use from the early 1800s to the mid-1900s, when the burning of coal was made illegal by the Clean Air Act. The coal hole hatch in our picture, by the way, is from an expensive street in Pimlico.

Loudon's Parents' Grave, in the graveyard of Pinner Parish Church, Middlesex.

In this remote churchyard in Pinner stands one of Loudon's lesser-known achievements - this most unusual gravestone which he designed for his father in 1809, with his mother also buried here in 1841. With the stone crib being projected some 50 ft towards heaven, it is a most unusual sight and well worth a visit.

John Claudius Loudon (1783–1843). Scottish-born agriculturist, encyclopaedist, landscape-gardener, horticulturist, editor of journals, the expert on cemeteries, architect and influential critic. Loudon settled in London in 1803. Within only a year after his arrival, his first book 'Observations on the Formation and Management of Useful and Ornamental Plantations, on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening' was published. Over the coming years, he became renowned for his landscape gardening and architectural work. In 1811 he invented an iron glazing-bar that made curved glazing possible and erected various prototype hot-houses incorporating his structural and other practical ideas. This Loudon invention made possible the more famous works by Paxton at Chatsworth and then again with London’s Great Exhibition of 1851 - and of course the magnificent Crystal Palace.

Gibson Square’s Temple

The Milner-Gibson family owned property in Theberton in Suffolk after making their fortune from plantations in Trinidad. Major Thomas Gibson died in 1807, leaving his one-year-old son, also Thomas, born in Trinidad, to develop their Islington estate when he was old enough. By the time Thomas had reached thirty, the building work had already started with Gibson and Milner Squares on his Islington fields.

Thomas Milner-Gibson the younger (1806-84) was also M.P. at various times for Ipswich, Manchester and Ashton-under-Lyne, becoming an active anti-Corn law campaigner and President of the Board of Trade.

The plans for Gibson Square were made by Francis Edwards showing the usual layout of central gardens surrounded by railings with locked gates, open to resident key holders only. By the 1930s the Square had become rather run down and the gardens up-keep was taken over by Islington Council. During World War II the gardens were dug up and air-raid shelters were installed. Afterwards, it was restored and maintained to its conventional design.

London Transport in 1963 was busy building the Victoria Line and needed a ventilation shaft in an open space. As the underground line runs beneath Gibson Square, it was considered a safe bet as the land belonged to the council, and it was thought an easy place to build without any neighbours opposing it. The proposal was to build a fifty-foot ventilating tower of a functional pleasant design. London Transport engineers were in for a big surprise from the now affluent owner-occupiers, who formed a society to fight this development tooth and nail for several years.

It was eventually decided to create a low-rise structure of a simulated temple with Pantheon overtones, designed by Raymond Erith and Quinlan Terry. Now with the passage of time, the mellowing brick-work has given this air-vent Georgian authenticity.

Crossing over London Bridge from the City of London, where the entrance to London Bridge Railway Station meets with the busy Borough High Street junction, there is a clock with weeds growing high above this derelict corner of London. If you observe the top of the clock just above the XII (12), you will notice the head complete with horns of what looks like a deer.

During the Second World War, a large number of civilian metal stretchers were stored ready for a large number of casualties. After the war, there was a problem with how to get rid of this huge amount of ironware. The problem was solved with the need to build more blocks of flats to house the homeless who had been bombed out. The stretchers were used as railings surrounding new estates like this one in Bermondsey.

St George the Martyr "Little Dorrit’s" church, giving Bermondsey a black look

St George the Martyr, “Little Dorrit’s church”, giving Bermondsey a black look

The first church of St. George, Southwark, was probably built at the beginning of the 12th century. The present church was authorised by Act of Parliament for the Building of Fifty New Churches. John Price designed the new church, with the foundation stone laid on St. George's Day, 1734. The main part of the structure was completed by 1735. The grant from the Commissioners proved inadequate to cover the cost of furnishing the church and in 1735 a rate of one shilling in the pound was levied to set up the old organ, provide a clock, font, etc. The church was opened in 1736 when numbered pew seats were allotted to 404 parishioners and their families. The clock with four dials in the steeple was made by George Clarke of Whitechapel for £90 in 1738. The clock is unusual in that one of its four faces is never illuminated and painted black. This came about because it faced the parish of Bermondsey, and when the church was asking for the one shilling donations from surrounding parishes, Bermondsey never gave a penny.

Dog And Pot

On the corner of Union Street and Blackfriars Road, just opposite Transport for London offices at Palestra, you might have noticed an effigy of a dog licking inside a pot.

The replica is a distinctive shop sign known to Charles Dickens and it was erected as part of the celebrations for the writer's bicentenary in 2012.

The original 'dog and pot' sign belonged to an ironmonger's, J. W. Cunningham & Co of 196 Blackfriars Road, and was mounted on a bracket that projected from the corner of the premises from the 18th century until 1931. Rowland Hill House now occupies the site of the shop, opposite Palestra.

Dickens passed it regularly in the 1820s as he walked home from his work in a blacking factory at Charing Cross to his lodging in Lant Street. The 'dog and pot' image was also depicted on coal plates that were made in Union Street.

The sign is referred to by Dickens in a letter he wrote to his friend and biographer John Forster in 1847 which features in the book “The Life of Charles Dickens”. He wrote: "My usual way home was over Blackfriars Bridge and down that turning in the Blackfriars Road which has Rowland Hill's Chapel on one side and the likeness of a golden dog licking a golden pot over a shop door on the other."

The sculpture is based on the original sign (the original brass and wood sign was sold in 1931 and is now on display in Southwark's Cuming Museum) carved in wood and stands on a bracket which is mounted on a tall reclaimed Victorian lamppost.

An inscription incised in stone on the ground in front of the post stands in a circular area defined by Victorian-style railings, with the gardens of Nelson Square behind.

I wonder if the bird perched on the dog's back knows what the dickens it’s doing there! I must admit it looks so much better than the CCTV camera mounted almost opposite!

Police Hook

The police hook in Great Newport Street is difficult to find, but if you persevere with your search, on the north side near the junction of Upper St Martins Lane, you will eventually locate it. The policeman's hook or cloak hanger dates back to the horse and carriage times and days of the early motor traffic, when police were called for point duty at busy junctions. We all know how quickly the weather changes so a cloak to shield from the rain was essential if you needed to stand around for ages. If the cloak wasn't needed, but hands were to direct the traffic, then a place to hang the garment was essential. In those long gone days there would have been plenty of busy cross roads with policemen's hooks, but due to this hard to see cloak hanger, thankfully it has been overlooked.

Bow Street Police Station

The Bow Street Police Station and Magistrates Court, home of the original Bow Street Runners, has a unique feature that no other London police station has. When blue lamps outside Bow Sreet police stations were first introduced in 1861, Queen Victoria was not too amused. She objected to seeing the blue lamps every time she visited the Royal Opera House in Covent Garden, for it reminded her of the blue room in which Prince Albert, her husband, had died. So the blue lamps were exchanged for white lamps, which have remained outside long after the police station was closed!

Slow Food

In 1894, George Gaudin founded L' Escargot in Greek Street, Soho. The French name for snail did not proclaim a speciality dish, rather worth eating, was worth waiting for. Above the name is George Gaudin riding a snail, a symbol of his belief in slow food.

Streets of London Paved With Gold

In 1894, George Gaudin founded L' Escargot in Greek Street, Soho. The French name for snail did not proclaim a speciality dish, rather worth eating, was worth waiting for. Above the name is George Gaudin riding a snail, a symbol of his belief in slow food.

Streets of London Paved With Gold

31 May 1578 Martin Frobisher sailed to Canada. Over time he brought home 1500 tons of 'gold ore'. It was merely worthless iron pyrite (fool's gold) later used to pave streets in London, leading to the myth that the streets of London were paved with gold.

London Time

Follow Us

The contents of this website are the property of knowledgeoflondon.com and therefore must not be reproduced without permission. Every effort is made to ensure the details contained on this website are correct, however, we cannot accept responsibility for errors and omissions.

© Copyright 2004 -

Contact Us | Advertise