The Marine Police Museum

London has plenty of museums, some of them large and well-known – others small and obscure. Within them, they hold a unique insight with collections and artefacts which many of us are already familiar with. I would like to enlighten you with one of the rarest; a museum which is certainly a hidden gem of London – not only a museum but also an active working environment where history is still being written.

Attached to the Metropolitan Police Marine Unit in Wapping High Street, is the museum of the marine police, which can only be viewed by special request. I contacted the trustee of the museum, a retired marine police officer Robert Jeffries, who allowed Knowledge of London an exclusive narrative of the history and mysteries surrounding the Thames River Police.

The Birth of the Police Force

Wapping is the spiritual home of policing as we know it today. People believe policing began with Sir Robert Peel’s police force in 1829, but the river police predate the “Bobbies” by some thirty-one years. Why did London need its own river police? The answer lies in the fact that during the late eighteenth century, London was the richest city in the world. All London’s trade was brought up the river to the legal docks, where every year 13,500 ships would unload their cargoes. Many of the loaders who removed the goods were “thieves” although they did not see themselves in quite that way; to them, it was plain and simple – one of the perks of the job!

Merchants of the West India Company during the 1790’s, operating the largest cargo fleets, were facing a serious problem. The pilfering of their cargoes was causing huge losses. It was estimated that £500,000 worth of goods each year was being stolen by the loaders – taking their perks! In today's money, this would equate to around £70 million per annum in losses – a whacking great some to lose.

Essex Justice of the Peace

Patrick Colquhoun

Master Mariner John Harriott devised a plan to curb the problem in 1797 along with Essex Justice of the Peace Patrick Colquhoun; they also procured the help, of a Scottish merchant, statistician, magistrate, and utilitarian philosopher, Jeremy Bentham.

Armed with Harriott’s proposal and Bentham’s insights, Colquhoun was able to persuade the West India Planters Committees and the West India Merchants to fund the new force. They agreed to a one-year trial and on the 2 July 1798, after receiving government permission, the Thames River Police began operating with Colquhoun as Superintending Magistrate and Harriott the Resident Magistrate.

With an initial investment of £4,200, the new force began with about 50 men charged with policing 33,000 workers in the river trades, of whom Colquhoun claimed 11,000 were known criminals and “on the game.” The river police received a hostile reception by riverfront workers not wishing to lose their supplementary income. A mob of 2,000 attempted to burn down the police office with the police inside. The skirmish that followed resulted in the first death in the line of duty for the new force, with the killing of Gabriel Franks.

The First Official Murder of a Police Officer

Kept in a glass cabinet in the museum, is the Roll of Honour, which contains the name of Gabriel Franks the first police officer ever to be murdered. The account what led up to his murder involved a perk of the job – coal!

Ships would arrive from Newcastle and the lumpers would unload them. Gabriel was a master lumper, a man in charge of a gang of lumpers and he was employed by the police. A ton of coal would be stolen by the heavers from each ship, submerging the sack into the river to make the coal wet and therefore if questioned by the police they would claim to have gathered up bits of coal, lost from the ships and found on the banks of the river.

On the 13 October, 1798 John Eyers plus two others were charged with the theft of coal and fined 20 shillings (£1). As they were leaving the court, John’s Brother James arrived and asked if they were fine; on hearing that they had been fined he told them to demand it back!

They threatened to set light to the place and to kill the magistrate. A riot ensued as stones and bricks were thrown at the courtroom in Wapping High Street. The doors were all bolted as the fire alarms rang out and Harriot ordered everyone upstairs.

Unlike today the early police force was heavily armed. They took up positions on the rooftop and commenced to shoot. One rioter was killed and the angry mob dispersed only to return and re-grouped.

At the same time Gabriel Franks had just come out of the nearby Rose and Crown public house in the company of some friends. Upon hearing the commotion, he made his way to the police office with two other men (Peacock and Web) and asked to be admitted. He tried to gain entry into the police station. He was told that no one was to leave or to enter and for some reason Gabriel started taking notes. He decided to go back to his pub and to arm himself with a cutlass, as he turned around he was mortally wounded by gunfire and died a week later.

The murderer was never found but James Eyres was charged with the murder of Gabriel Franks, on the grounds that he started the riots. He was found guilty at the Old Baily on the 9th January 1799 and sentenced to death by hanging.

Nevertheless, Colquhoun reported to his backers that his force was a success after its first year, and his men had “established their worth by saving £122,000 worth of cargo and by the rescuing of several lives.”

Word of this success spread quickly, and the government passed the Marine Police Bill on 28th July 1800, transforming it from private to a public police agency. Colquhoun published a book on the experiment; The Commerce and Policing of the River Thames. It found receptive audiences far outside London and inspired similar forces being established in other countries, notably New York, Dublin and Sydney.

The Marine Police Force continues to operate from the same Wapping High Street address. The Thames Magistrates Court also originated in this building. In 1839 the force merged with the Metropolitan Police Force to become Thames Division, and is now known as the Marine Support Unit of the Metropolitan Police Service.

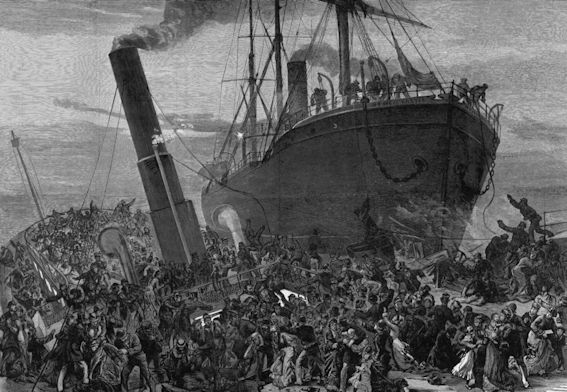

Greatest Tragedy on the Thames

On September 3, 1878, SS Princess Alice, a passenger paddle steamer was sunk in a collision on the River Thames with the collier Bywell Castle off Tipcock Point (near the present day Thames Barrier) with the loss of over 650 lives, the greatest loss of life in any Thames shipping disaster. The Princess Alice was making what was billed as a “Moonlight Trip” to Gravesend and back. This was a routine trip from Swan Pier, Swan Lane E.C.4 to Gravesend and Sheerness. Tickets were sold for two shillings (10p).

By 7:40pm, the Princess Alice was on her return journey and within sight of the North Woolwich Pier – where many passengers were to disembark – when she sighted the Newcastle bound SS Bywell Castle which had just been repainted at a dry dock and was on her way to pick up a load of coal. Her Master was Captain Harrison, who was accompanied by an experienced Thames river pilot. Harrison was following the traditional routes used on the Thames instead of the 1872 rule about passing oncoming vessels on the port side.

Bywell Castle and Princess Alice accident

On the bridge of the Bywell Castle, Harrison observed the Princess Alice coming across his bow, making for the north side of the river, he set a course to pass astern of her. The Master of the Princess Alice, 47-year old Captain William R.H Grinstead, was confused by this and altered Princess Alice’s course, bringing her into the path of Bywell Castle. Captain Harrison ordered his ship’s engines reversed, but it was too late. Princess Alice was struck on the starboard side, she split in two and sank within four minutes.

Many passengers were trapped within the wreck and drowned; piles of bodies were found around the exits of the saloon when the wreck was raised. Additionally, the twice-daily release of 75 million imperial gallons of raw London sewage from sewer outfalls at Barking and Crossness had occurred one hour before the collision: the heavily polluted water was believed to have contributed to the deaths of those who went into the river. It was noted that the sunken corpses began rising to the surface after only six days, rather than the usual nine. Between 69 and 170 people were rescued: but tragically over 650 died. 120 victims were buried in a mass grave at Woolwich Old Cemetery, Kings Highway, Plumstead. A memorial cross was erected to mark the spot, “paid for by national sixpenny subscriptions to which more than 23,000 persons contributed.”

The Marine Police Museum has the only remaining artefact from the Princess Alice, the company ensign of the Princess Alice (1878), found by William Grinstead’s grandson with the same name.

Thames Division’s Waterloo Pier, situated next to Waterloo Bridge, was the only floating police station in the world. The present pontoon was constructed in 1873 (now the RNLI lifeboat pier Victoria Embankment).

Officers based at Waterloo Pier patrolled the Thames from Tower Bridge to Richmond. The base played an important role in the policing of London because of its strategic location.

Another floating base was established at Blackwall opposite the present day 02 Arena. When a vessel was anchored here it was termed as being ‘Stationed’ from where the words ‘Police Station’ originate from. Rowers would work a 6 hour on and 12 hours off shift. The rowers would patrol to the beat of their oars – and this is where we get the words ‘patrolling the beat’ from.

Boat named after river police founder Master Mariner John Harriott

Today the River Police are concentrated more on river security with so many potential targets. Take for example riverside locations, the House of Commons, MI5 and MI6 and all the bridges crossing the Thames – all potential terrorists’ targets. The primary objects of policing are; number one to save life; number two stopping crime, and number three detecting crime.

The Thames River Police Museum

The Thames River Police Museum

London Time

The contents of this website are the property of knowledgeoflondon.com and therefore must not be reproduced without permission. Every effort is made to ensure the details contained on this website are correct, however, we cannot accept responsibility for errors and omissions.

The contents of this website are the property of knowledgeoflondon.com and therefore must not be reproduced without permission. Every effort is made to ensure the details contained on this website are correct, however, we cannot accept responsibility for errors and omissions. Contact Us | Advertise

Contact Us | Advertise